For years, Canada has grappled with a devastating overdose crisis, with thousands of people succumbing to the lethal effects of toxic drugs, particularly fentanyl. However, while fatal overdoses have rightly garnered attention, a second, lesser-known crisis is emerging: the long-term impacts of non-fatal overdoses. These events, though not deadly, can leave survivors with lasting, life-altering injuries, placing additional pressure on an already strained healthcare system. The toll of these overdoses, especially on vulnerable populations, is profound, and the numbers reveal the scale of the problem.

Fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid, is the primary culprit behind the deadly wave of overdoses. Used medically as a painkiller, fentanyl can have a powerful sedative effect on the body. However, when taken recreationally, it becomes exceedingly dangerous. The drug acts on the brainstem, which controls the body’s breathing, and in the case of an overdose, fentanyl binds to receptors in this part of the brain, often causing breathing to slow or stop altogether. The risk of overdose is high, and without immediate intervention, such as Naloxone, the consequences are frequently fatal. But what happens to those who survive these close calls?

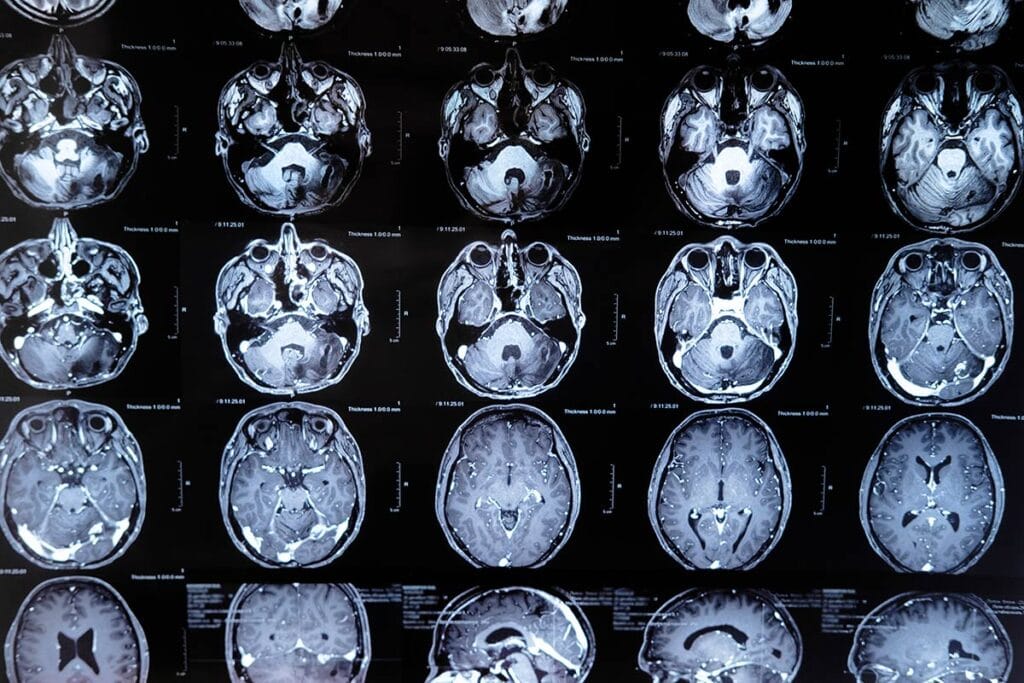

Research shows that for every fatal overdose, there are an estimated 15 to 20 non-fatal overdoses. In Canada, this translates to staggering numbers—while 44,000 people have died from fatal overdoses since 2016, more than 650,000 non-fatal overdoses have occurred. These incidents are often accompanied by severe, sometimes irreversible, injuries, with brain damage being one of the most concerning outcomes. During an overdose, breathing becomes shallow or may stop entirely, cutting off oxygen to the brain. Neurons, which rely on oxygen to function, can be permanently damaged in just a few minutes, resulting in hypoxic brain injuries.

The Lasting Impact of Hypoxic Brain Injury

Hypoxic brain injury, caused by a lack of oxygen during an overdose, has severe consequences. People who survive an overdose may experience cognitive impairments, including memory loss, difficulty with attention and decision-making, and even motor coordination issues. These deficits make it exceedingly challenging for survivors, particularly those already grappling with substance use disorders, to manage their daily lives or pursue recovery. As many frontline workers have observed, non-fatal overdoses often lead to significant neurological damage that complicates addiction treatment.

Studies from British Columbia in 2023, which analyzed health data from 824,000 people, found that individuals who experienced an overdose were 15 times more likely to have also sustained a hypoxic brain injury. These injuries may not always be immediately apparent, and in many cases, survivors of overdoses do not receive proper neurological assessments. Another federal study from 2019 to 2020, which looked at over 4,000 opioid-related hospitalizations, found that 4.2% of those admitted for drug overdoses were also diagnosed with hypoxic brain injuries. However, experts believe this figure underestimates the true extent of the problem, as many overdose victims do not seek hospital care or are not evaluated for brain damage.

The potential effects of these injuries are profound. Survivors may suffer from emotional dysregulation, cognitive delays, and impaired problem-solving abilities—issues that significantly hinder their ability to manage addiction and participate in rehabilitation programs. One particularly troubling condition linked to opioid overdoses is an amnestic syndrome, which affects the hippocampus, the part of the brain responsible for memory. This syndrome, along with other cognitive deficits like reduced verbal fluency and processing speed, has made recovery more difficult for people with opioid use disorder (OUD).

Challenges in Treating Survivors of Non-Fatal Overdoses

The long-term impacts of brain damage from non-fatal overdoses present a growing challenge for healthcare providers and addiction treatment programs. For many survivors, the cognitive impairments caused by hypoxic injuries make it challenging to follow structured treatment plans, such as those involving methadone or other medication-assisted therapies. Individuals with brain injuries may struggle with the daily task of attending treatment appointments or even remembering to take their medications.

Rob Boyd, the director of Inner City Health in Ottawa, has highlighted the difficulties these patients face. Methadone treatment, a proven method for managing opioid addiction, requires patients to return for treatment day after day consistently. For people who have suffered brain injuries, this level of consistency can be nearly impossible. Without specialized programs designed to address these cognitive challenges, many survivors of non-fatal overdoses fall through the cracks, unable to engage fully in their recovery.

The scope of the problem is vast. Despite some efforts to improve care for survivors of non-fatal overdoses, gaps in the system persist. Neuropsychologist Mauricio Garcia-Barrera, a leading expert on this issue in Canada, has called for routine assessments of overdose survivors to check for brain injuries. He believes that early intervention is crucial for improving outcomes. By identifying and addressing cognitive impairments sooner, healthcare providers can offer more tailored treatments that help survivors regain their independence and better manage their substance use disorders.

Government Action

As the overdose crisis continues, provincial governments across Canada are grappling with how to address the unique needs of overdose survivors. In British Columbia, Premier David Eby has proposed opening rehabilitation facilities to provide involuntary care for individuals who are both brain-injured and struggling with severe addiction. This plan, which would operate under the authority of the Mental Health Act, has sparked intense debate. Proponents argue that involuntary care may be the only way to ensure that severely affected individuals receive the help they need, but critics worry about the ethical implications of forcing treatment on people who may not be able to consent.

Meanwhile, in Ontario, Premier Doug Ford has focused on the role of supervised consumption sites in preventing overdose deaths and injuries. Ford’s government has expressed concerns about crime and social disorder around these sites, even pledging to close some. However, advocates argue that these sites are essential for preventing the very brain injuries that are becoming more common among survivors of non-fatal overdoses. Within supervised consumption sites, staff can administer Naloxone quickly, often preventing the respiratory depression that leads to hypoxia and brain damage. As no deaths have occurred within these sites, proponents argue that they are crucial in harm reduction and should be expanded, not closed.

A Struggling System and the Road Ahead

The challenges faced by survivors of non-fatal overdoses are complex, and Canada’s healthcare system is struggling to keep up. Many frontline workers report that they are increasingly acting as “second brains” for their clients, helping them manage day-to-day tasks that have become insurmountable due to brain injuries. The cognitive and emotional difficulties faced by overdose survivors complicate efforts to treat addiction and contribute to a sense of social disorder in communities like Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES), where public drug use and related issues have escalated in recent years.

Beyond simply saving lives, the focus must shift toward comprehensive care that includes early neurological assessments, long-term rehabilitation, and specialized addiction treatments tailored for individuals with cognitive impairments. The need for integrated healthcare solutions is urgent, as brain injuries from overdoses complicate the path to recovery and require a multi-faceted approach. Investing in neurorehabilitation services, training healthcare professionals to recognize and treat brain damage, and ensuring sustained follow-up care are essential steps toward mitigating the broader impacts of the overdose crisis on both individuals and the healthcare system at large. Without such targeted interventions, the healthcare burden will continue to grow, leaving survivors of non-fatal overdoses at greater risk of long-term disability and diminishing their chances of a meaningful recovery.

Kris has been at the forefront of Downtown Eastside initiatives for over 15 years, working to improve the neighbourhood. As a consultant to several organizations, he played a key role in shaping harm reduction strategies and drug policies. A strong proponent of decisive action, Kris’s work focuses on driving tangible change and advocating for solutions that address the complex challenges facing the community.

Leave a Comment