The notion of safer supply, once seen as a beacon of hope in Canada’s battle against the opioid crisis, is now sparking widespread debate. Intended to combat overdose deaths and curb the spread of disease, safer supply programs provide regulated, pharmaceutical-grade alternatives to illicit drugs. But as the stories from British Columbia unfold, it becomes clear that these programs are not without their challenges. Teens as young as 12 are increasingly exposed to diverted safer supply drugs, leading to dangerous dependencies. The question remains: how safe is “safe supply” when it’s making its way onto the streets, far from the hands of healthcare providers?

While designed to save lives, safer supply may also be inadvertently fueling youth addiction and creating a secondary market for drugs intended to be safe. This article explores the promise and pitfalls of safer supply programs, with a focus on the tragedy of Kamilah Sword, whose untimely death raises important questions about how these programs are regulated and their impact on vulnerable populations.

What Is Safer Supply?

Safer supply programs, introduced in Canada to combat the rising overdose deaths, are based on the idea that providing regulated, pharmaceutical-grade drugs to people with opioid use disorder can prevent overdose deaths and reduce the harmful effects of drug addiction. In contrast to unregulated street drugs, which are often tainted with lethal substances like fentanyl, safer supply offers a controlled alternative that allows users to manage their addiction under medical supervision. The goals are to reduce overdose fatalities, connect people to healthcare, and prevent the spread of infectious diseases like HIV.

The safer supply strategy represents a shift in thinking—moving away from punitive measures that treat addiction as a crime and towards a public health approach. In British Columbia, a province hit hardest by the opioid epidemic, safer supply programs were expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic to help people avoid street drugs at a time when isolation, mental health issues, and limited access to healthcare heightened the risks of drug use.

But what happens when safer supply drugs find their way onto the streets? For families like that of Kamilah Sword, the answer is tragic.

Kamilah Sword: A Life Lost to Diversion

Kamilah Sword from Port Coquitlam was just 15 years old when she died from a drug overdose. A high school student with dreams of a bright future, Kamilah’s life began to spiral out of control during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Isolated from her friends and community, she turned to online spaces to connect with new people, eventually experimenting with drugs alongside her peers.

As her father, Gregory Sword, recalls, Kamilah’s drug use escalated over time. At first, it seemed like typical teenage rebellion—experimenting with alcohol and smoking. But soon, it became something far more dangerous. She and her friends began using hydromorphone, a drug more commonly known as Dilaudid, which they were able to easily purchase from individuals who had obtained the drug through safer supply programs.

Hydromorphone was not a street drug mixed with fentanyl or other toxins. It was a pharmaceutical-grade opioid, handed out through government-sanctioned safer supply programs, designed to provide people with safe alternatives to street drugs. But for Kamilah, hydromorphone—referred to by teens as “dillies”—was far from safe.

Gregory Sword recounts how his daughter and her friends would travel to Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES), a neighbourhood known for its entrenched drug crisis, to buy these drugs from individuals on safer supply. They would pay as little as $5 per pill, using money earned from odd jobs or allowances. For these teenagers, safer supply drugs were not a way to manage addiction—they were a way to get high cheaply and easily.

One evening, after returning home from seeing friends, Kamilah was found dead in her room, curled up in the fetal position. The coroner’s report indicated that she had a mix of drugs in her system, including small amounts of cocaine, MDMA, and hydromorphone. Her father had never heard of hydromorphone before her death, and like many parents, he was unaware of how easily teens could access these drugs.

Saving Lives or Creating New Addicts?

Kamilah’s story brings to the forefront a growing debate around safer supply programs. On one side, advocates argue that safer supply saves lives by providing people with alternatives to the toxic street drugs responsible for most overdoses. The intent is to reduce the harm caused by unpredictable drug markets and to engage people in healthcare, offering a path away from addiction. Indeed, safer supply programs in places like the Downtown Eastside have been credited with reducing overdose deaths among the most vulnerable populations.

Yet, the other side of the debate questions the unintended consequences of these programs—specifically, drug diversion and the potential for creating new addictions among youth. Gregory Sword and other families affected by diversion argue that hydromorphone, intended to be part of a harm-reduction program, ended up fueling the opioid dependencies of teens like Kamilah.

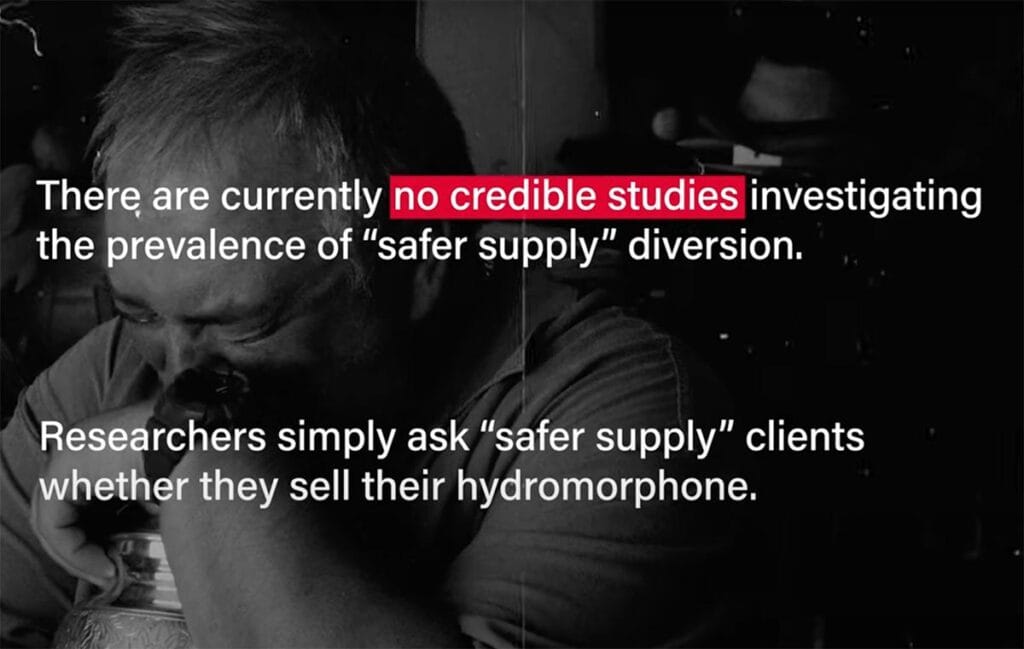

Hydromorphone, known for its potency, is a commonly prescribed opioid in safer supply programs. It’s also a drug that is easily diverted to the illegal market. According to reports from the Vancouver Police Department, approximately 50% of hydromorphone seizures in the city are linked to diverted safer supply. In cities like Ottawa, similar patterns have emerged, with law enforcement observing an increase in diverted safer supply drugs entering the street market.

While public health officials continue to defend the overall effectiveness of safer supply, the personal stories of youth accessing these diverted drugs paint a different picture. The teens interviewed in the documentary “Government Heroin 2: The Invisible Girls” spoke candidly about how safer supply drugs were often easier to obtain than alcohol. They described how adults would sell hydromorphone to them outside pharmacies or in Vancouver’s DTES. One teen, Madison, recalls walking around the neighbourhood with her friends and hearing drug dealers and others openly advertising “dillies” for sale. Before long, her entire friend group was hooked.

Regulation and Oversight

So how do we address the risks posed by drug diversion without abandoning the life-saving potential of safer supply programs? Public health officials and harm reduction advocates argue that while diversion exists, it remains an isolated problem that does not outweigh the benefits of providing people with safer, regulated alternatives to street drugs. They emphasize that without safer supply, more people would be using dangerous, unpredictable substances, leading to even higher rates of overdose.

Yet, stories like Kamilah’s demand a more nuanced response. Critics argue that the current lack of oversight in safer supply programs allows too much room for diversion. While methadone and Suboxone programs require strict monitoring, frequent check-ins, and supervised doses, safer supply recipients are often given large quantities of pills to take home at once, creating opportunities for misuse and resale.

One potential solution is to tighten regulations around how safer supply drugs are distributed. Some advocates suggest that these medications should be dispensed in smaller quantities or only at supervised consumption sites, where individuals can use the drugs in a controlled setting. This would reduce the likelihood of diversion while still providing access to safer alternatives for those who need them.

Another solution is to increase access to addiction treatment services, such as detox and rehab, to ensure that individuals using safer supply have a clear path to recovery. For families like the Swords, the lack of immediate, affordable treatment options meant that Kamilah’s dependency spiralled out of control before she had a chance to seek help.

The Downtown Eastside Connection

The Downtown Eastside plays a significant role in both the safer supply debate and the tragedy of Kamilah Sword. Long considered the heart of Vancouver’s overdose crisis, the DTES is home to some of the country’s most innovative harm reduction initiatives, including Canada’s first supervised injection site, Insite, and widespread naloxone distribution programs. These initiatives are credited with saving countless lives by reducing overdose deaths in the area.

However, the DTES also exemplifies the challenges of safer supply. In this neighbourhood, drugs like hydromorphone circulate widely, both legally through programs and illegally through diversion. The teens who shared their stories described how they would travel from the suburbs to the DTES to buy diverted safer supply drugs. For many youth, the DTES became a hub for acquiring cheap opioids, creating new addictions that would later spiral into the use of harder drugs like fentanyl.

The tension in the DTES reflects the broader national conversation about harm reduction: while initiatives like safer supply are necessary to save lives, they also come with the risk of creating new paths to addiction if not properly regulated.

Regulation, Not Rejection

While the debate around safer supply continues to heat up, the question is not whether safer supply should exist, but rather how it should be regulated. Both advocates and critics agree that the current system needs more oversight to prevent the kinds of tragedies we’re seeing in British Columbia. Public health officials have largely defended the program, pointing to the overall reduction in overdose deaths as evidence of its success. It is clear that changes are needed. Stricter regulations, such as limiting take-home doses or requiring supervised consumption, would help curb the potential for diversion while still maintaining the life-saving benefits of safer supply.

At the same time, more investment is needed in addiction treatment and recovery services. For people like Kamilah, the opportunity to get help before addiction takes hold is often the difference between life and death. Without accessible, affordable treatment options, families are left to navigate the crisis alone, often with devastating consequences.

A Complicated Solution to a Complex Problem

Kamilah Sword’s death is a sobering reminder that while safer supply may save lives, it is not without risks. The safer supply debate is far from over. On one side are those who argue that safer supply saves lives by offering a regulated alternative to fentanyl-laced street drugs. On the other are families like Gregory’s, who have watched their children die after being exposed to diverted drugs. The truth likely lies somewhere in between.

There is no easy answer to the opioid crisis, but one thing is clear: we cannot continue to ignore the growing number of youth being exposed to these drugs. Safer supply programs must be reevaluated, and more robust safeguards must be put in place to prevent drug diversion. Until then, the tragic stories of teens like Kamilah will continue to haunt British Columbia’s streets.

In the end, how safe is “safe supply” when it becomes just another drug on the street?

Kris has been at the forefront of Downtown Eastside initiatives for over 15 years, working to improve the neighbourhood. As a consultant to several organizations, he played a key role in shaping harm reduction strategies and drug policies. A strong proponent of decisive action, Kris’s work focuses on driving tangible change and advocating for solutions that address the complex challenges facing the community.

Leave a Comment