British Columbia’s overdose crisis continues to dominate political discourse, and the BC Conservative Party finds itself at the centre of a controversy over its stance on supervised drug consumption sites. These facilities, which have existed since 2003 and withstood legal challenges, are now caught in a storm of conflicting political messages. The BC Conservatives appear to be sending mixed signals on whether they would close these sites—sometimes referred to as “drug dens”—or allow them to continue under a new guise. At the core of this debate lies an existential question about harm reduction and whether the government should intervene in how addiction services are provided.

A Shifting Message

The BC Conservatives have oscillated between outright condemnation of these supervised consumption and overdose prevention sites (OPS) and more cautious rhetoric about transitioning them. The story took a new turn when Elenore Sturko, incumbent South Surrey MLA and a prominent BC Conservative voice, attempted to clarify the party’s intentions. While leader John Rustad declared that his party would shut down all government-sanctioned consumption sites, labeling them as “drug dens,” Sturko quickly walked back this extreme position, emphasizing a slower, more strategic approach.

“We want to transition our sites into access hubs for services including treatment and medical center services,” said Sturko. “We’re certainly not suddenly locking the doors. That’s not what this is about. This is about transitioning people, not medicating them.” Her remarks sparked even more confusion, as they seemed at odds with Rustad’s declaration just days earlier that the party would “shut down all government-sanctioned drug den injection sites.”

A Lifeline or a Failed Experiment?

Supervised consumption sites (SCS) and overdose prevention sites (OPS) have long been a contentious issue in Canada, particularly in British Columbia, where they first opened two decades ago. These facilities are designed to provide a safe environment for drug users, reduce overdose deaths, and offer access to health services. Their presence in the province is rooted in a landmark 2011 Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) decision, which allowed the operation of these sites, despite opposition from the federal government. In that ruling, the high court emphasized that shutting down such facilities would result in a disproportionate risk of death and disease to drug users. It was clear: SCS saves lives.

However, BC Conservatives argue that these sites perpetuate addiction rather than solving the problem. Rustad’s characterization of these sites as “failed experiments” frames them as hubs of criminal activity and a threat to community safety. His bold rhetoric resonates with many who believe that current harm reduction strategies have failed to curtail drug use and overdose deaths. But is this view backed by evidence?

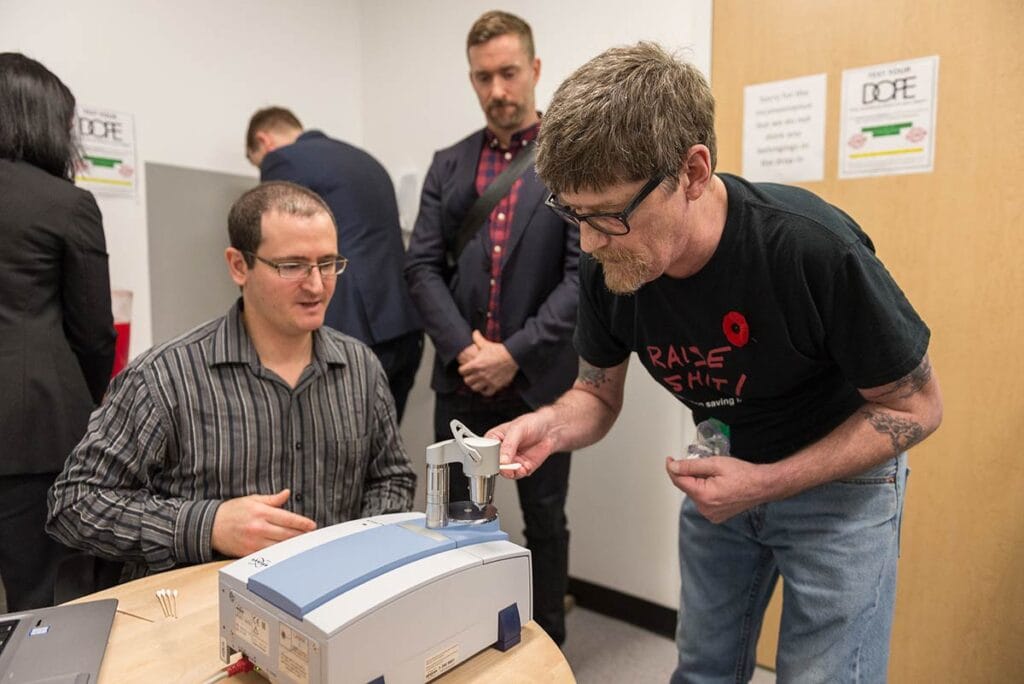

According to health experts and numerous studies, including the 2011 Supreme Court decision, these sites are not just places for drug consumption but also centers for addiction treatment, mental health support, and medical care. For instance, Insite, North America’s first supervised consumption site located in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, has been shown to reduce overdose deaths, decrease the transmission of diseases like HIV, and provide a bridge to rehabilitation services. Pivot Legal Society’s 2023 count showed there are three SCS and 54 OPS throughout B.C., with eight located in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

The Legal Tightrope

One glaring issue for the BC Conservatives is the legal precedent protecting these sites. The Supreme Court’s decision in Canada (Attorney General) vs. Portland Hotel Society was definitive: consumption sites save lives, and their constitutional right to exist cannot be easily revoked. Andrew Longhurst, a health policy researcher at Simon Fraser University, expressed skepticism that Rustad’s promises of closure would withstand legal challenges. “The fact he [Rustad] is taking this position makes me wonder if he’s aware of the SCC decision or not,” Longhurst stated, noting that a renewed court battle would likely be costly and fail to deliver the results Rustad anticipates.

This leaves the BC Conservatives in a precarious position. If they cannot legally close these sites, could they “starve” them of funding instead? Critics argue that this could be the party’s next move, gradually reducing the resources available to these facilities until they are no longer able to function effectively. The question remains: how far will the party go to push its agenda in a landscape dominated by complex legal protections?

A Growing Crisis

Behind this political theater is a devastating reality: B.C. is in the midst of an overdose crisis unlike anything the province has seen before. In 2022, 2,511 people died from drug overdoses in the province, a rate of 45.7 per 100,000 residents, marking the highest overdose mortality rate in Canada. Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, was detected in 83% of these deaths. The staggering rise in overdose deaths—from 7.2 per 100,000 in 2013 to the current rate—has been attributed primarily to the increasing toxicity of street drugs.

Sonia Furstenau, leader of the BC Green Party, was quick to criticize the Conservatives’ approach. She argued that closing down consumption sites would not address the root cause of the crisis: the toxic drug supply. “The other parties are proposing solutions that do nothing to end the toll that drugs being distributed by organized crime in BC are having on our communities,” Furstenau said, further highlighting the flaws in the Conservatives’ strategy.

The Future of Harm Reduction in B.C.

As the opioid crisis deepens, the political landscape in British Columbia is being reshaped by starkly different views on how to tackle this public health emergency. The NDP and Green Party support maintaining and expanding these supervised sites as critical lifelines in the fight against overdose deaths. Meanwhile, the Conservatives are pushing a hard-line approach that seeks to dismantle these services, albeit with little consensus within the party on how or when to do so.

The debate about SCS and OPS is emblematic of a broader ideological divide—between those who see harm reduction as essential to saving lives and those who view it as enabling addiction. With over 2,500 overdose deaths annually and no signs of the crisis abating, the question remains: how will B.C. navigate this deadly terrain?

One thing is certain—the fate of supervised drug consumption sites will remain a hot-button issue for years to come, as political leaders wrestle with life-and-death decisions for thousands of vulnerable citizens. What do you think? Should the government prioritize harm reduction, or is it time for a new approach?

DOWNTOWNEASTSIDE.ORG is a collective author account used by several DTES contributors to discuss key issues and events in the neighbourhood. Articles under this authorship reflect diverse perspectives from those directly connected to the community. If you’d like to reach a specific contributor, please contact us via email.

Leave a Comment