Maternal health has long been a cornerstone of public health policy in Canada, yet an unsettling gap persists in how we address maternal deaths caused by suicide and drug overdose. While these deaths remain largely absent from national maternal mortality statistics, a growing body of evidence suggests they constitute a significant and underreported public health crisis. A recent study published in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada sheds light on this issue, focusing on British Columbia and Ontario, two provinces where systemic challenges and alarming patterns come into sharp relief.

Data Gaps and Alarming Findings

National maternal mortality statistics in Canada traditionally emphasize physical complications, such as hemorrhage or infection, sidelining mental health crises. Yet the study reveals that between 2017 and 2019, 35 maternal deaths due to suicide or overdose were recorded in Ontario and British Columbia alone. Nine of these deaths occurred in BC, with the majority classified as accidental overdoses involving polysubstance use. Notably, fentanyl was implicated in most cases, often alongside substances like methamphetamines and benzodiazepines.

These findings are striking not only for their numbers but also for what they reveal about the lives of the deceased. The study highlights recurring themes of instability, trauma, and inadequate support systems. Many of these women experienced pre-existing mental health disorders—such as anxiety, bipolar disorder, or borderline personality disorder—and lived with the compounded stress of poverty, housing insecurity, and lack of familial or community support.

Critically, the study underscores how these deaths are often concentrated in populations already marginalized by systemic inequities. Women who died from overdose or suicide frequently lived in shelters, battled unemployment, or had histories of domestic violence or child apprehension. The absence of a partner or stable housing was a common thread across most cases, painting a stark picture of socio-economic vulnerability.

The Intersection of Mental Health and Substance Use

The intersection of mental health and substance use is another critical dimension revealed by the study. Among the overdose deaths in BC, nearly all women had documented histories of substance use, yet only three received care related to mental health or addiction during or after pregnancy. This glaring gap suggests systemic neglect in addressing the dual challenges of addiction and perinatal mental health disorders.

One particularly troubling finding is that pregnancy-related factors exacerbate existing vulnerabilities. The study notes that modifications to psychopharmacological treatments during pregnancy often left women inadequately supported. For instance, some women stopped taking medications to avoid potential harm to their babies, leading to worsening mental health symptoms. Combined with the physical and emotional toll of pregnancy or miscarriage, these disruptions created a dangerous tipping point.

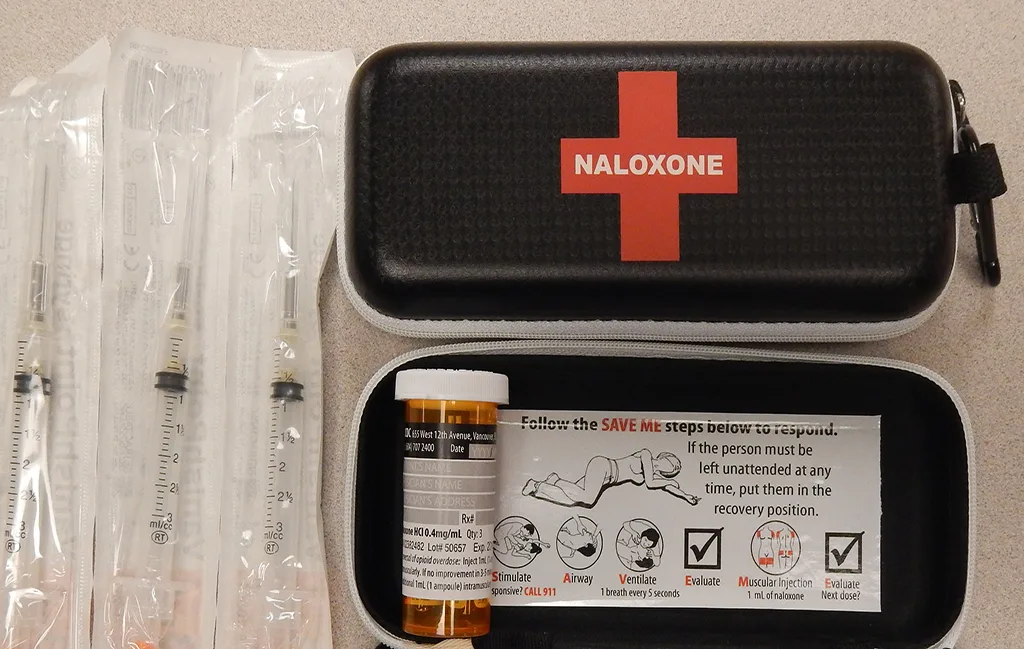

The Downtown Eastside, one of BC’s most vulnerable communities, exemplifies women’s challenges in navigating these crises. This area is characterized by a toxic drug supply increasingly laced with dangerous additives like xylazine, an animal tranquillizer. For pregnant and postpartum women, this unpredictability heightens the risks of accidental overdose. Tragically, these deaths often occur outside healthcare settings, where interventions might be possible.

A Systemic Blind Spot

Perhaps the most troubling revelation is how Canada’s healthcare system systematically overlooks these deaths. Suicide and overdose are rarely classified as maternal deaths in official statistics, a categorization that obscures their prevalence and prevents targeted interventions. The absence of a centralized database compounds this issue, leaving researchers reliant on regional studies or fragmented coroners’ reports.

Even within BC’s healthcare system, resources tailored to pregnant and postpartum women who use substances are sparse. Programs like the Families in Recovery (FIR) initiative at BC Women’s Hospital demonstrate the potential for comprehensive care, but such services are far from widespread. This gap leaves many women without access to the wraparound support they need to navigate the challenges of addiction and motherhood.

Moreover, the stigma surrounding maternal mental health and substance use often deters women from seeking help. Many fear losing custody of their children or being judged by healthcare providers, further isolating them during critical periods. This stigma is compounded by the systemic inequities faced by marginalized populations, including Indigenous women, who disproportionately experience trauma and barriers to care.

A National Epidemic

While this investigation focuses on British Columbia, the patterns it reveals reflect a broader Canadian crisis. Historical data from other provinces reinforces the study’s findings. For example, Alberta reported that one in five maternal deaths between 1998 and 2015 was linked to suicide or drug toxicity, and Ontario data from 1994 to 2008 shows similar trends.

These deaths occur disproportionately among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, underscoring the role of systemic inequities in shaping maternal outcomes. Rural and remote areas are particularly affected, where access to mental health and addiction services is limited or nonexistent. For women in these regions, seeking help often requires travelling long distances, a logistical and financial burden many cannot afford.

This geographic disparity highlights the urgent need for a cohesive, national approach to maternal mental health and addiction care. Without it, the true scale of maternal deaths by suicide and overdose will remain hidden, and efforts to address the crisis will continue to fall short.

Reflecting on Maternal Overdose Mortality

Behind the statistics lie lives disrupted by the intersections of trauma, addiction, and motherhood—an intricate web we, as a society, too often fail to untangle until it’s too late. This crisis challenges the idea of maternal mortality as a mere clinical term. It’s a reminder that motherhood is not only about life-giving but also about survival in a world that often overlooks the invisible burdens of caregiving and sacrifice. It questions the structures we take for granted—the healthcare systems, societal norms, and safety nets—that let these women slip through the cracks.

Acknowledging this issue means understanding that maternal health extends far beyond the delivery room. It encompasses the support systems that nurture mental well-being, the community scaffolding that holds women through loss, and the medical expertise that adapts with empathy. In the truest sense, a mother’s survival depends on more than her body—it depends on a collective societal will to prioritize her humanity.

As Canadians, we often pride ourselves on fairness and inclusivity. But the silence surrounding maternal deaths from suicide and overdose is a stark reminder that our progress is uneven. The story doesn’t end with these findings but begins anew with the conversations they ignite. Every mother’s life is a testament to resilience. Every death we fail to prevent is a call to interrogate the systems we allow to persist. Canada must decide whether these stories remain hidden beneath the surface—or whether we use them to build something better.

Monika is a dedicated Downtown Eastside activist and youth counsellor with extensive experience working alongside British Columbia and California community organizations. Passionate about harm reduction and youth empowerment, Monika’s advocacy focuses on creating impactful programs, offering a voice to those often overlooked.

Leave a Comment